(Also available in CODAP)

Students analyze their class' snacking habits in comparison with data on childhood obesity in the U.S. This project supports the learning goals of our lesson on The Data Cycle.

Lesson Goals |

Students will be able to…

|

Student-facing Lesson Goals |

|

Materials |

|

Preparation |

|

Facilitation Note |

|

Project Origins |

|

🔗Building a Data Set: Our Snacking Habits flexible

Overview

Students track their snacking habits over the course of 5 days to generate a collective data set. In preparation, they’ll identify the data types of each variable. By revisiting the spreadsheet the class is generating throughout the data collection phase, you’ll have an opportunity to discuss what it means to clean a data set.

Note: This phase of the project should be started right away, but does not need to be completed before moving on to the Researching U.S. Snacking Habits phase of this project.

Launch

As a result of advocacy, food packaging is required to provide consumers with nutritional information so we can make informed choices.

We’re going to track our snacking habits for 5 days to generate a collective dataset that we can analyze. Once we have that collective dataset, each student will create a slide deck sharing charts and reflections about our snacking habits.

To help students understand the scope of the project, some teachers find it useful to walk students through the slide template and distribute copies of the Snack Habits Rubric.

For our purposes, a snack is any food or beverage other than water that you consume between meals.

For each snack that you consume over the next 5 days you will be reading the Nutrition Facts on the labels (or googling for them) in order to enter a number of data points into a google form.

-

Let’s turn to Snack Habits Data and take a look at the kinds of data we’ll be collecting.

-

Record your notices and wonders on the space provided in question 1.

(We encourage you to have students share them out before moving on!) -

With your partner complete the third column of the table by deciding what data type each variable will be.

Confirm that students have correctly identified the data types.

Make sure you’ve made a copy of this Google form and shared a link with your students.

-

Your task is to complete the google form for every snack you eat over the next 5 days.

-

Please save the link I shared with you somewhere that will be easy for you to find.

-

Suggestions might include: In "Notes" on your phone? In a text message? In an email?

-

-

If you eat a snack when you don’t have time to fill out the form, please take a picture of it and/or make a note to help you fill out the form later on.

-

We will be looking at the spreadsheet together in our next class to see how our dataset is shaping up.

You may want to have students complete Snack Habits Check-In part way through the data collection process. This Check-In form can help keep students accountable, especially if you discuss students' responses and problem-solve as a class.

Investigate

To access your class' data:

-

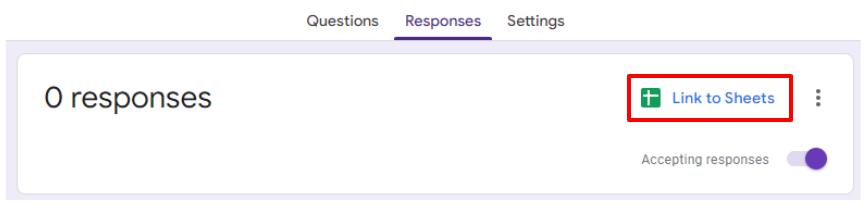

Link the Google Form Responses to a Google Sheet by selecting the Responses tab and then clicking the button that reads Link to Sheet. (Screenshot below.) The sheet will automatically continue to populate the Google Sheet each time the form gets submitted.

-

When your class is done collecting data,

-

duplicate the sheet in a new tab

-

name the new tab "cleaned"

-

remove the timestamp column (and the image column if you decided to add it to the form)

-

make sure the sharing settings are set to "Anyone with the link can view"

-

copy the url into the Snack Data Starter File Template to import the data, publish the file and share a link with your students

-

We have set the form up with data verification for most questions to minimize the amount of cleaning you will have to do, but we would expect that the one word answers to "Why are you eating this snack?" will require some attention as there will likely be:

-

typos

-

inconsistent capitalization

-

words that mean the same thing as each other and should be combined

-

nonsense words that might make more sense to be replaced by "idk" why I’m snacking?

If you have the time, we encourage you to project the spreadsheet and clean the data with your students, asking:

-

What inconsistencies do you see in the data?

-

How should we address them?

Ideally, by the time you’re done you could make a pie-chart of the "why" column and the breakdown of reasons would be informative.

Let’s spend some time reflecting on the work we have completed so far.

-

Make your own copy of this slide template.

-

On slide 3, reflect on what you’ve learned by tracking your snack consumption.

-

On slides 4 and 5, reflect on what you Notice and Wonder about the class dataset.

And now, let’s see what we can learn about our habits!

-

Open the starter file I shared with you and use it to complete Data Cycle: Distribution of Categorical Columns.

-

As you work, save any displays of interest to your slide deck in Part 3: My Research Question. It’s okay to save more displays than you will be able to use.

-

When you’re done:

-

Choose one display you found particularly interesting to add to slide 6.

-

Put your Data Cycle: Distribution of Categorical Columns somewhere safe because you’ll need it to complete your slide deck later on.

-

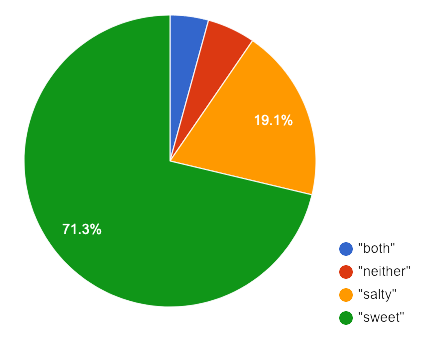

For reference, here’s an example of a display from one Bootstrap teacher’s class. Consider the kinds of discussions your class might have if the data from your class came back looking like this. For instance:

-

Why do you think sweet snacks were so much more popular than salty snacks in our class?

-

Do you think this trend (more sweet snacks than salty) will hold when we look at other classes? How about when we zoom out and consider a larger population?

-

A very small proportion of our snacks were neither salty nor sweet. Why do you think these snacks were less popular?

Synthesize

-

What did you learn as you interpreted the distribution of categorical columns?

-

What new questions do you have?

🔗Research: U.S. Snacking Habits Data

Overview

Students will gather information from studies about U.S. snacking habits and compare them to the data we’ve just gathered as a class.

Launch

Do you think the sample we’ve made of our snack habits is representative of snacking in the United States?

We don’t have to guess! There’s plenty of research out there for us to look at. In fact, enough data has been collected about childhood obesity in the United States that soda machines and unhealthy snacks have been pulled from many schools.

-

Let’s turn our attention to Part 2: Preliminary Research.

-

Open your favorite search engine (Google, Brave, DuckDuckGo, etc.) and type "American snacking habits”. Look for statistics that come from credible sources and relate to the kinds of data we’re collecting about our snack habits (e.g., time of day, snack flavor, nutrition information, reason for the snack).

-

As you work, be sure to save links along with the information you find in this section of the slide deck, adding as many slides as you need.

-

Start a new search for "American snacking habits charts". This time go to the Images tab to look for displays. Follow the same criteria as before regarding credibility and relevance.

Some students may benefit from a class discussion of what makes a source credible. Invite students to consider the following questions: When was the data collected? What is the purpose of the display? Is it free from bias?

You may choose to keep this conversation brief or dig deeper. Our lesson on Threats to Validity offers some guidance for teachers and students interested in exploring this topic further.

Investigate

Let’s compare and contrast your findings from our class data with the research you’ve been doing about U.S. snack habits.

-

Choose a graph or statistic of particular relevance and credibility.

-

Complete U.S. Snack Habits.

-

Then complete Part 3: U.S. Snacking Habits of your slide deck.

-

If you have time, duplicate the slides in Part 3: U.S. Snacking Habits and add additional graphs or statistics.

Invite students to share their thoughts and reflections. Students will be developing a statistical questions in the final phase of the project. Consider making a class list of any interesting statistical questions that emerge during class discussion.

Synthesize

-

Think about the process you went through to collect snacking data. What were the steps?

-

Now, consider the data collection process used to create the graphs and charts you found through your internet search. What steps do you think were taken?

-

Compare and contrast the data collection processes:

How were the samples chosen?

How are the samples alike?

How are they different?

Which charts do you think contain more credible data—the ones we built in Pyret, or the ones you found through your internet search? Why?

🔗Analysis: A Statistical Question of Your Own

Overview

Building on their explorations of the class data and initial research about U.S. Snacking habits, students develop a statistical question to present their findings on.

Launch

Now that you’ve had some time to explore both our class data and the research that’s been done about snacking habits in the U.S., it’s time to identify a statistical question that is of particular interest to you and present your findings.

Remember - a statistical question is often best asked with "in general" attached, because we expect some variability and the answer isn’t black and white.

-

Ensure that all of the work you have completed so far is on hand. This includes: (1) Data Cycle: Distribution of Categorical Columns, (2) U.S. Snack Habits, (3) your class dataset, (4) your slide deck.

-

As you revisit the items listed above, make a list of any statistical questions that pop into your mind.

-

Share your favorite possible questions with a partner; discuss which question will make for the most interesting project.

-

Once you have decided on a question, type it into Part 4: My Research Question of your slide deck.

Investigate

-

Complete the remaining slides in Part 4: My Research Question of the slide deck, adding any additional slides that are needed.

-

Then complete the slides in Part 5: Conclusions and Sources.

Once finished, encourage students to self-assess and revise their work. If time allows, peer review using the Snack Habits Rubric can be a valuable activity.

Synthesize

-

What were the pros and cons of working with data generated by you and your classmates?

-

What other data do you wish had been part of our collective data set? What other questions would you suggest adding to the form?

-

Decide what form of sharing their projects works best for you.

-

Class presentations can instill a sense of pride.

-

Presenting in small groups can take less time.

-

You may also want to have them print some part of their presentation to display on a bulletin board.

-

-

Did your students have brilliant suggestions for how we could improve the form for future classes? Please share your ideas with us at mailto:contact@bootstrapworld.org!

These materials were developed partly through support of the National Science Foundation, (awards 1042210, 1535276, 1648684, 1738598, 2031479, and 1501927).  Bootstrap by the Bootstrap Community is licensed under a Creative Commons 4.0 Unported License. This license does not grant permission to run training or professional development. Offering training or professional development with materials substantially derived from Bootstrap must be approved in writing by a Bootstrap Director. Permissions beyond the scope of this license, such as to run training, may be available by contacting contact@BootstrapWorld.org.

Bootstrap by the Bootstrap Community is licensed under a Creative Commons 4.0 Unported License. This license does not grant permission to run training or professional development. Offering training or professional development with materials substantially derived from Bootstrap must be approved in writing by a Bootstrap Director. Permissions beyond the scope of this license, such as to run training, may be available by contacting contact@BootstrapWorld.org.